Pedestrians now walk faster and linger less, researchers find

A computer vision study compares changes in pedestrian behavior since 1980, providing information for urban designers about creating public spaces.

City life is often described as “fast-paced.” A new study suggests that’s more true that ever.

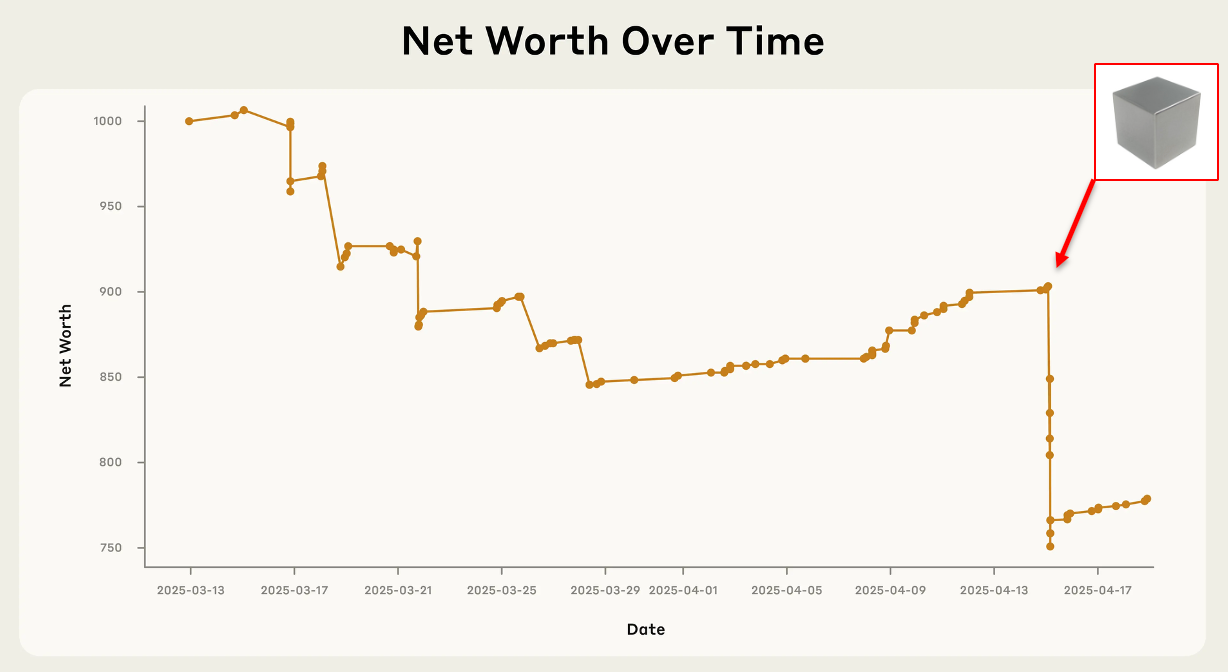

The research, co-authored by MIT scholars, shows that the average walking speed of pedestrians in three northeastern U.S. cities increased 15 percent from 1980 to 2010. The number of people lingering in public spaces declined by 14 percent in that time as well.

The researchers used machine-learning tools to assess 1980s-era video footage captured by renowned urbanist William Whyte, in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. They compared the old material with newer videos from the same locations.

“Something has changed over the past 40 years,” says MIT professor of the practice Carlo Ratti, a co-author of the new study. “How fast we walk, how people meet in public space — what we’re seeing here is that public spaces are working in somewhat different ways, more as a thoroughfare and less a space of encounter.”

The paper, “Exploring the social life of urban spaces through AI,” is published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The co-authors are Arianna Salazar-Miranda MCP ’16, PhD ’23, an assistant professor at Yale University’s School of the Environment; Zhuanguan Fan of the University of Hong Kong; Michael Baick; Keith N. Hampton, a professor at Michigan State University; Fabio Duarte, associate director of the Senseable City Lab; Becky P.Y. Loo of the University of Hong Kong; Edward Glaeser, the Fred and Eleanor Glimp Professor of Economics at Harvard University; and Ratti, who is also director of MIT’s Senseable City Lab.

The results could help inform urban planning, as designers seek to create new public areas or modify existing ones.

“Public space is such an important element of civic life, and today partly because it counteracts the polarization of digital space,” says Salazar-Miranda. “The more we can keep improving public space, the more we can make our cities suited for convening.”

Meet you at the Met

Whyte was a prominent social thinker whose famous 1956 book, “The Organization Man,” probing the apparent culture of corporate conformity in the U.S., became a touchstone of its decade.

However, Whyte spent the latter decades of his career focused on urbanism. The footage he filmed, from 1978 through 1980, was archived by a Brooklyn-based nonprofit organization called the Project for Public Spaces and later digitized by Hampton and his students.

Whyte chose to make his recording at four spots in the three cities combined: Boston’s Downtown Crossing area; New York City’s Bryant Park; the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, a famous gathering point and people-watching spot; and Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street.

In 2010, a group led by Hampton then shot new footage at those locations, at the same times of day Whyte had, to compare and contrast current-day dynamics with those of Whyte’s time. To conduct the study, the co-authors used computer vision and AI models to summarize and quantify the activity in the videos.

The researchers have found that some things have not changed greatly. The percentage of people walking alone barely moved, from 67 percent in 1980 to 68 percent in 2010. On the other hand, the percentage of individuals entering these public spaces who became part of a group declined a bit. In 1980, 5.5 percent of the people approaching these spots met up with a group; in 2010, that was down to 2 percent.

“Perhaps there’s a more transactional nature to public space today,” Ratti says.

Fewer outdoor groups: Anomie or Starbucks?

If people’s behavioral patterns have altered since 1980, it’s natural to ask why. Certainly some of the visible changes seem consistent with the pervasive use of cellphones; people organize their social lives by phone now, and perhaps zip around more quickly from place to place as a result.

“When you look at the footage from William Whyte, the people in public spaces were looking at each other more,” Ratti says. “It was a place you could start a conversation or run into a friend. You couldn’t do things online then. Today, behavior is more predicated on texting first, to meet in public space.”

As the scholars note, if groups of people hang out together slightly less often in public spaces, there could be still another reason for that: Starbucks and its competitors. As the paper states, outdoor group socializing may be less common due to “the proliferation of coffee shops and other indoor venues. Instead of lingering on sidewalks, people may have moved their social interactions into air-conditioned, more comfortable private spaces.”

Certainly coffeeshops were far less common in big cities in 1980, and the big chain coffeeshops did not exist.

On the other hand, public-space behavior might have been evolving all this time regardless of Starbucks and the like. The researchers say the new study offers a proof-of-concept for its method and has encouraged them to conduct additional work. Ratti, Duarte, and other researchers from MIT’s Senseable City Lab have turned their attention to an extensive survey of European public spaces in an attempt to shed more light on the interaction between people and the public form.

“We are collecting footage from 40 squares in Europe,” Duarte says. “The question is: How can we learn at a larger scale? This is in part what we’re doing.”