Decoding the Arctic to predict winter weather

With the help of AI, MIT Research Scientist Judah Cohen is reshaping subseasonal forecasting, with the goal of extending the lead time for predicting impactful weather.

Every autumn, as the Northern Hemisphere moves toward winter, Judah Cohen starts to piece together a complex atmospheric puzzle. Cohen, a research scientist in MIT’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE), has spent decades studying how conditions in the Arctic set the course for winter weather throughout Europe, Asia, and North America. His research dates back to his postdoctoral work with Bacardi and Stockholm Water Foundations Professor Dara Entekhabi that looked at snow cover in the Siberian region and its connection with winter forecasting.

Cohen’s outlook for the 2025–26 winter highlights a season characterized by indicators emerging from the Arctic using a new generation of artificial intelligence tools that help develop the full atmospheric picture.

Looking beyond the usual climate drivers

Winter forecasts rely heavily on El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) diagnostics, which are the tropical Pacific Ocean and atmosphere conditions that influence weather around the world. However, Cohen notes that ENSO is relatively weak this year.

“When ENSO is weak, that’s when climate indicators from the Arctic becomes especially important,” Cohen says.

Cohen monitors high-latitude diagnostics in his subseasonal forecasting, such as October snow cover in Siberia, early-season temperature changes, Arctic sea-ice extent, and the stability of the polar vortex. “These indicators can tell a surprisingly detailed story about the upcoming winter,” he says.

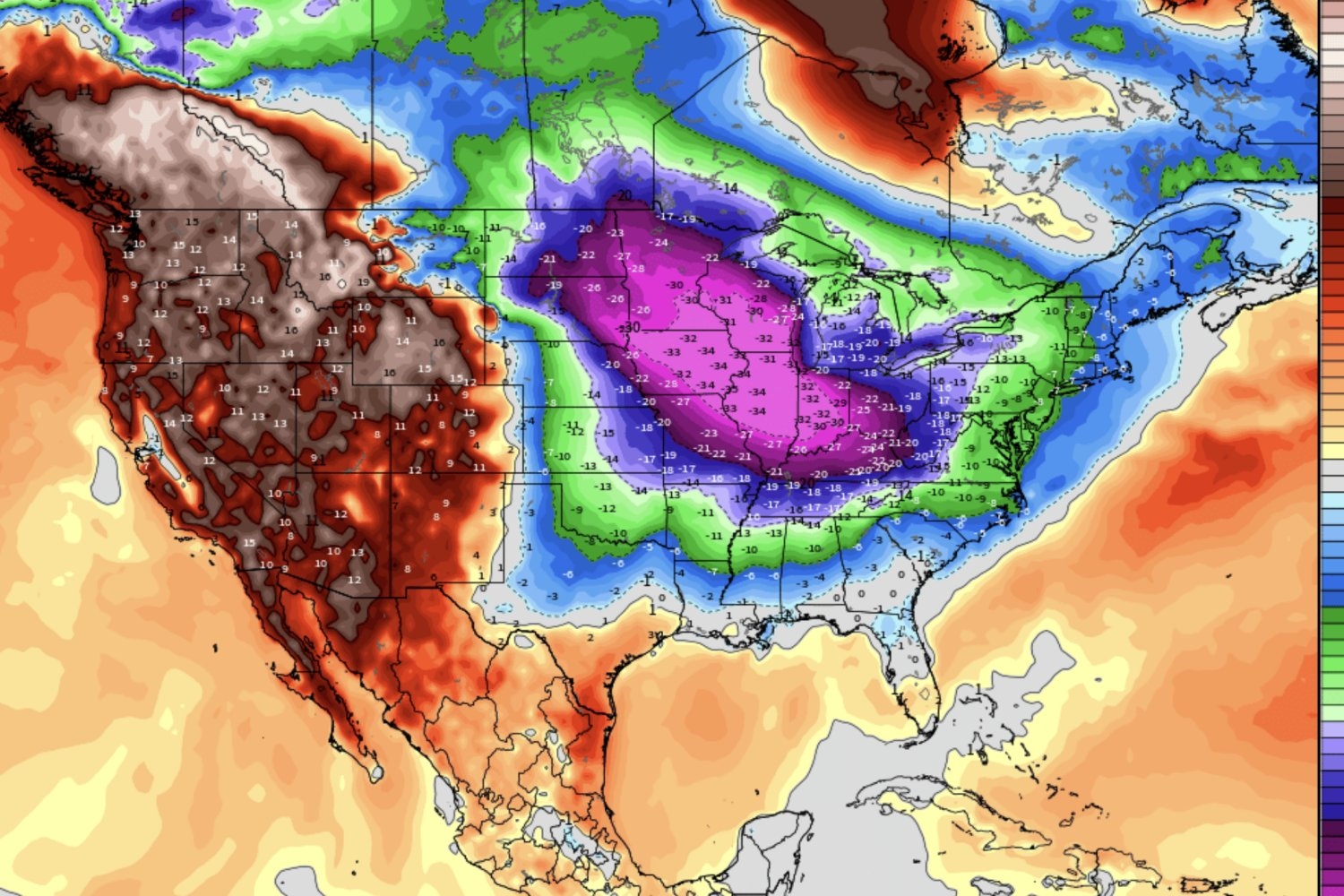

One of Cohen’s most consistent data predictors is October’s weather in Siberia. This year, when the Northern Hemisphere experienced an unusually warm October, Siberia was colder than normal with an early snow fall. “Cold temperatures paired with early snow cover tend to strengthen the formation of cold air masses that can later spill into Europe and North America,” says Cohen — weather patterns that are historically linked to more frequent cold spells later in winter.

Warm ocean temperatures in the Barents–Kara Sea and an “easterly” phase of the quasi-biennial oscillation also suggest a potentially weaker polar vortex in early winter. When this disturbance couples with surface conditions in December, it leads to lower-than-normal temperatures across parts of Eurasia and North America earlier in the season.

AI subseasonal forecasting

While AI weather models have made impressive strides showcasing in short-range (one-to–10-day) forecasts, these advances have not yet applied to longer periods. The subseasonal prediction covering two to six weeks remains one of the toughest challenges in the field.

That gap is why this year could be a turning point for subseasonal weather forecasting. A team of researchers working with Cohen won first place for the fall season in the 2025 AI WeatherQuest subseasonal forecasting competition, held by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). The challenge evaluates how well AI models capture temperature patterns over multiple weeks, where forecasting has been historically limited.

The winning model combined machine-learning pattern recognition with the same Arctic diagnostics Cohen has refined over decades. The system demonstrated significant gains in multi-week forecasting, surpassing leading AI and statistical baselines.

“If this level of performance holds across multiple seasons, it could represent a real step forward for subseasonal prediction,” Cohen says

The model also detected a potential cold surge in mid-December for the U.S. East Coast much earlier than usual, weeks before such signals typically arise. The forecast was widely publicized in the media in real-time. If validated, Cohen explains, it would show how combining Arctic indicators with AI could extend the lead time for predicting impactful weather.

“Flagging a potential extreme event three to four weeks in advance would be a watershed moment,” he adds. “It would give utilities, transportation systems, and public agencies more time to prepare.”

What this winter may hold

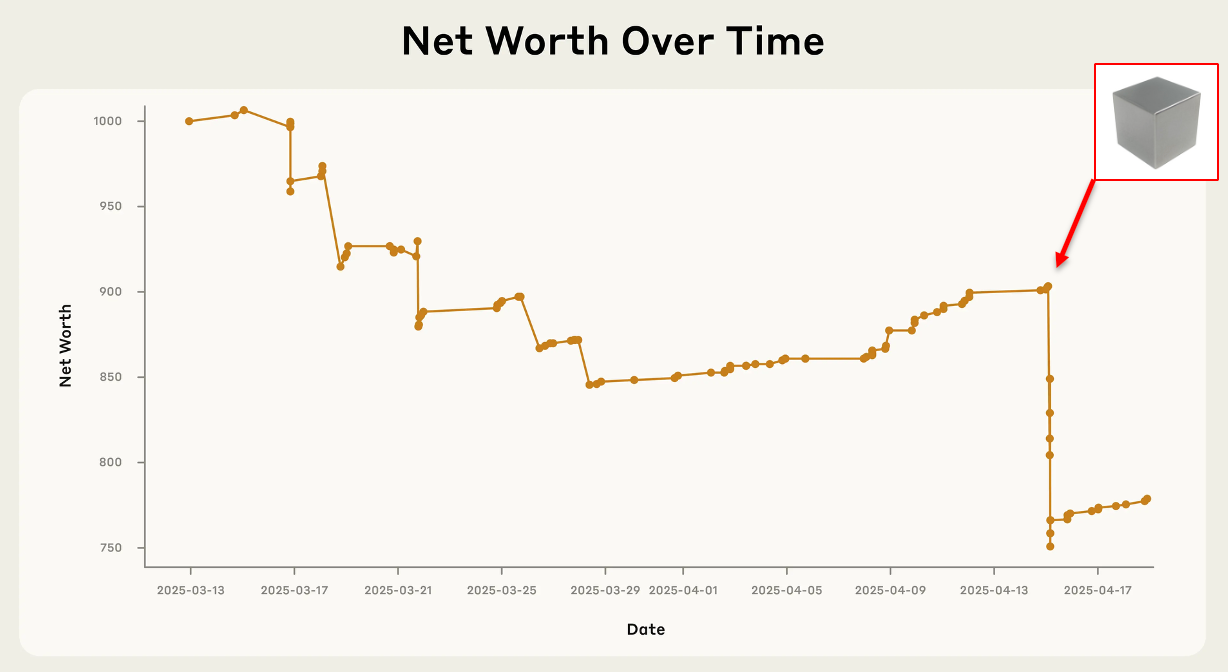

Cohen’s model shows a greater chance of colder-than-normal conditions across parts of Eurasia and central North America later in the winter, with the strongest anomalies likely mid-season.

“We’re still early, and patterns can shift,” Cohen says. “But the ingredients for a colder winter pattern are there.”

As Arctic warming speeds up, its impact on winter behavior is becoming more evident, making it increasingly important to understand these connections for energy planning, transportation, and public safety. Cohen’s work shows that the Arctic holds untapped subseasonal forecasting power, and AI may help unlock it for time frames that have long been challenging for traditional models.

In November, Cohen even appeared as a clue in The Washington Post crossword, a small sign of how widely his research has entered public conversations about winter weather.

“For me, the Arctic has always been the place to watch,” he says. “Now AI is giving us new ways to interpret its signals.”

Cohen will continue to update his outlook throughout the season on his blog.