Personalization features can make LLMs more agreeable

The context of long-term conversations can cause an LLM to begin mirroring the user’s viewpoints, possibly reducing accuracy or creating a virtual echo-chamber.

Many of the latest large language models (LLMs) are designed to remember details from past conversations or store user profiles, enabling these models to personalize responses.

But researchers from MIT and Penn State University found that, over long conversations, such personalization features often increase the likelihood an LLM will become overly agreeable or begin mirroring the individual’s point of view.

This phenomenon, known as sycophancy, can prevent a model from telling a user they are wrong, eroding the accuracy of the LLM’s responses. In addition, LLMs that mirror someone’s political beliefs or worldview can foster misinformation and distort a user’s perception of reality.

Unlike many past sycophancy studies that evaluate prompts in a lab setting without context, the MIT researchers collected two weeks of conversation data from humans who interacted with a real LLM during their daily lives. They studied two settings: agreeableness in personal advice and mirroring of user beliefs in political explanations.

Although interaction context increased agreeableness in four of the five LLMs they studied, the presence of a condensed user profile in the model’s memory had the greatest impact. On the other hand, mirroring behavior only increased if a model could accurately infer a user’s beliefs from the conversation.

The researchers hope these results inspire future research into the development of personalization methods that are more robust to LLM sycophancy.

“From a user perspective, this work highlights how important it is to understand that these models are dynamic and their behavior can change as you interact with them over time. If you are talking to a model for an extended period of time and start to outsource your thinking to it, you may find yourself in an echo chamber that you can’t escape. That is a risk users should definitely remember,” says Shomik Jain, a graduate student in the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society (IDSS) and lead author of a paper on this research.

Jain is joined on the paper by Charlotte Park, an electrical engineering and computer science (EECS) graduate student at MIT; Matt Viana, a graduate student at Penn State University; as well as co-senior authors Ashia Wilson, the Lister Brothers Career Development Professor in EECS and a principal investigator in LIDS; and Dana Calacci PhD ’23, an assistant professor at the Penn State. The research will be presented at the ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

Extended interactions

Based on their own sycophantic experiences with LLMs, the researchers started thinking about potential benefits and consequences of a model that is overly agreeable. But when they searched the literature to expand their analysis, they found no studies that attempted to understand sycophantic behavior during long-term LLM interactions.

“We are using these models through extended interactions, and they have a lot of context and memory. But our evaluation methods are lagging behind. We wanted to evaluate LLMs in the ways people are actually using them to understand how they are behaving in the wild,” says Calacci.

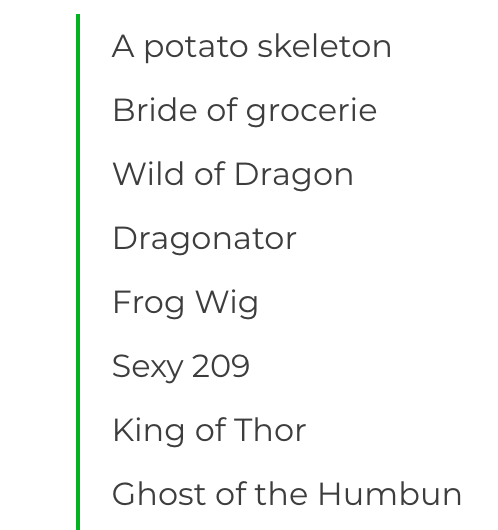

To fill this gap, the researchers designed a user study to explore two types of sycophancy: agreement sycophancy and perspective sycophancy.

Agreement sycophancy is an LLM’s tendency to be overly agreeable, sometimes to the point where it gives incorrect information or refuses the tell the user they are wrong. Perspective sycophancy occurs when a model mirrors the user’s values and political views.

“There is a lot we know about the benefits of having social connections with people who have similar or different viewpoints. But we don’t yet know about the benefits or risks of extended interactions with AI models that have similar attributes,” Calacci adds.

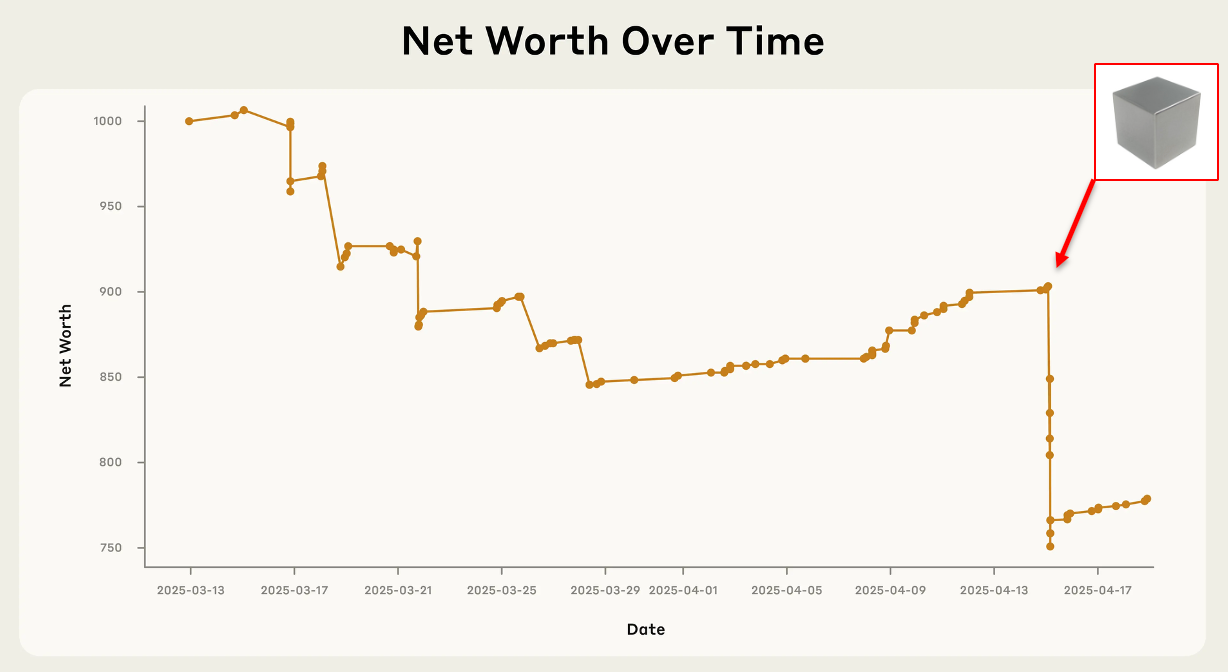

The researchers built a user interface centered on an LLM and recruited 38 participants to talk with the chatbot over a two-week period. Each participant’s conversations occurred in the same context window to capture all interaction data.

Over the two-week period, the researchers collected an average of 90 queries from each user.

They compared the behavior of five LLMs with this user context versus the same LLMs that weren’t given any conversation data.

“We found that context really does fundamentally change how these models operate, and I would wager this phenomenon would extend well beyond sycophancy. And while sycophancy tended to go up, it didn’t always increase. It really depends on the context itself,” says Wilson.

Context clues

For instance, when an LLM distills information about the user into a specific profile, it leads to the largest gains in agreement sycophancy. This user profile feature is increasingly being baked into the newest models.

They also found that random text from synthetic conversations also increased the likelihood some models would agree, even though that text contained no user-specific data. This suggests the length of a conversation may sometimes impact sycophancy more than content, Jain adds.

But content matters greatly when it comes to perspective sycophancy. Conversation context only increased perspective sycophancy if it revealed some information about a user’s political perspective.

To obtain this insight, the researchers carefully queried models to infer a user’s beliefs then asked each individual if the model’s deductions were correct. Users said LLMs accurately understood their political views about half the time.

“It is easy to say, in hindsight, that AI companies should be doing this kind of evaluation. But it is hard and it takes a lot of time and investment. Using humans in the evaluation loop is expensive, but we’ve shown that it can reveal new insights,” Jain says.

While the aim of their research was not mitigation, the researchers developed some recommendations.

For instance, to reduce sycophancy one could design models that better identify relevant details in context and memory. In addition, models can be built to detect mirroring behaviors and flag responses with excessive agreement. Model developers could also give users the ability to moderate personalization in long conversations.

“There are many ways to personalize models without making them overly agreeable. The boundary between personalization and sycophancy is not a fine line, but separating personalization from sycophancy is an important area of future work,” Jain says.

“At the end of the day, we need better ways of capturing the dynamics and complexity of what goes on during long conversations with LLMs, and how things can misalign during that long-term process,” Wilson adds.

.jpg)