AI simulation gives people a glimpse of their potential future self

By enabling users to chat with an older version of themselves, Future You is aimed at reducing anxiety and guiding young people to make better choices.

Have you ever wanted to travel through time to see what your future self might be like? Now, thanks to the power of generative AI, you can.

Researchers from MIT and elsewhere created a system that enables users to have an online, text-based conversation with an AI-generated simulation of their potential future self.

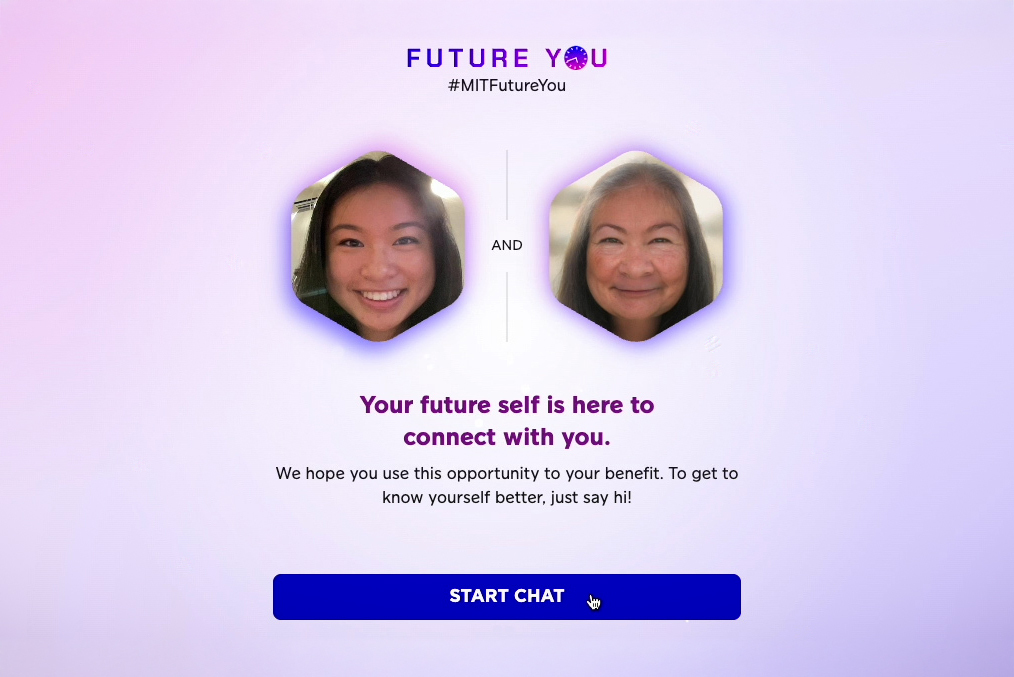

Dubbed Future You, the system is aimed at helping young people improve their sense of future self-continuity, a psychological concept that describes how connected a person feels with their future self.

Research has shown that a stronger sense of future self-continuity can positively influence how people make long-term decisions, from one’s likelihood to contribute to financial savings to their focus on achieving academic success.

Future You utilizes a large language model that draws on information provided by the user to generate a relatable, virtual version of the individual at age 60. This simulated future self can answer questions about what someone’s life in the future could be like, as well as offer advice or insights on the path they could follow.

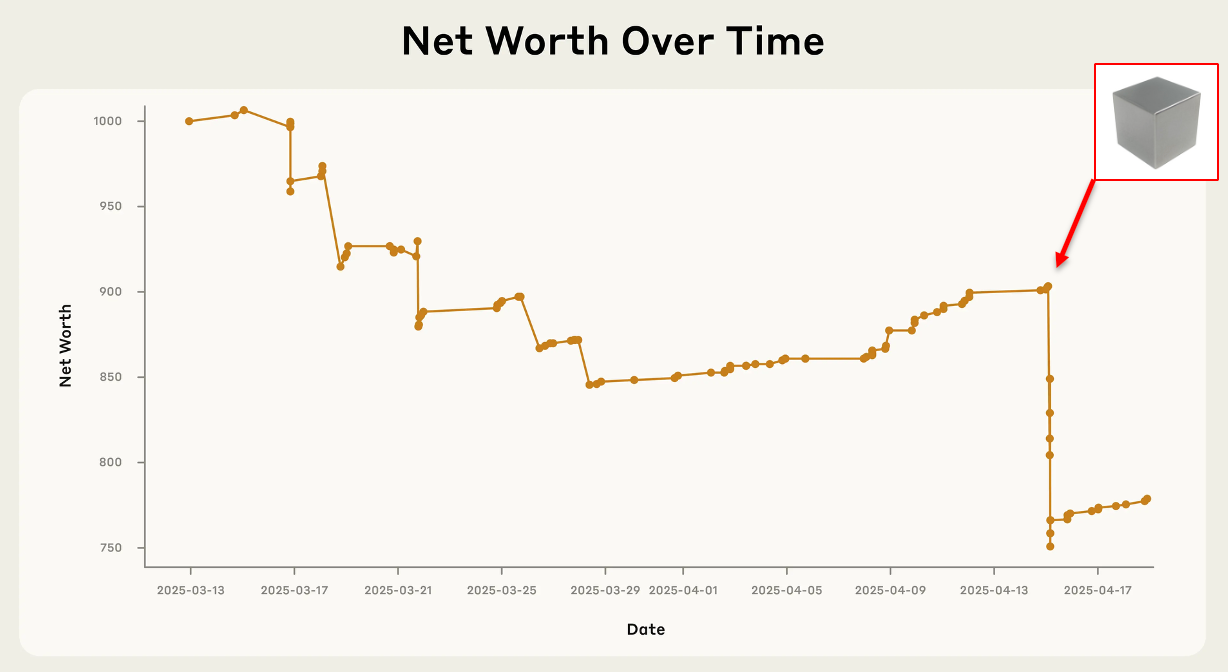

In an initial user study, the researchers found that after interacting with Future You for about half an hour, people reported decreased anxiety and felt a stronger sense of connection with their future selves.

“We don’t have a real time machine yet, but AI can be a type of virtual time machine. We can use this simulation to help people think more about the consequences of the choices they are making today,” says Pat Pataranutaporn, a recent Media Lab doctoral graduate who is actively developing a program to advance human-AI interaction research at MIT, and co-lead author of a paper on Future You.

Pataranutaporn is joined on the paper by co-lead authors Kavin Winson, a researcher at KASIKORN Labs; and Peggy Yin, a Harvard University undergraduate; as well as Auttasak Lapapirojn and Pichayoot Ouppaphan of KASIKORN Labs; and senior authors Monchai Lertsutthiwong, head of AI research at the KASIKORN Business-Technology Group; Pattie Maes, the Germeshausen Professor of Media, Arts, and Sciences and head of the Fluid Interfaces group at MIT, and Hal Hershfield, professor of marketing, behavioral decision making, and psychology at the University of California at Los Angeles. The research will be presented at the IEEE Conference on Frontiers in Education.

A realistic simulation

Studies about conceptualizing one’s future self go back to at least the 1960s. One early method aimed at improving future self-continuity had people write letters to their future selves. More recently, researchers utilized virtual reality goggles to help people visualize future versions of themselves.

But none of these methods were very interactive, limiting the impact they could have on a user.

With the advent of generative AI and large language models like ChatGPT, the researchers saw an opportunity to make a simulated future self that could discuss someone’s actual goals and aspirations during a normal conversation.

“The system makes the simulation very realistic. Future You is much more detailed than what a person could come up with by just imagining their future selves,” says Maes.

Users begin by answering a series of questions about their current lives, things that are important to them, and goals for the future.

The AI system uses this information to create what the researchers call “future self memories” which provide a backstory the model pulls from when interacting with the user.

For instance, the chatbot could talk about the highlights of someone’s future career or answer questions about how the user overcame a particular challenge. This is possible because ChatGPT has been trained on extensive data involving people talking about their lives, careers, and good and bad experiences.

The user engages with the tool in two ways: through introspection, when they consider their life and goals as they construct their future selves, and retrospection, when they contemplate whether the simulation reflects who they see themselves becoming, says Yin.

“You can imagine Future You as a story search space. You have a chance to hear how some of your experiences, which may still be emotionally charged for you now, could be metabolized over the course of time,” she says.

To help people visualize their future selves, the system generates an age-progressed photo of the user. The chatbot is also designed to provide vivid answers using phrases like “when I was your age,” so the simulation feels more like an actual future version of the individual.

The ability to take advice from an older version of oneself, rather than a generic AI, can have a stronger positive impact on a user contemplating an uncertain future, Hershfield says.

“The interactive, vivid components of the platform give the user an anchor point and take something that could result in anxious rumination and make it more concrete and productive,” he adds.

But that realism could backfire if the simulation moves in a negative direction. To prevent this, they ensure Future You cautions users that it shows only one potential version of their future self, and they have the agency to change their lives. Providing alternate answers to the questionnaire yields a totally different conversation.

“This is not a prophesy, but rather a possibility,” Pataranutaporn says.

Aiding self-development

To evaluate Future You, they conducted a user study with 344 individuals. Some users interacted with the system for 10-30 minutes, while others either interacted with a generic chatbot or only filled out surveys.

Participants who used Future You were able to build a closer relationship with their ideal future selves, based on a statistical analysis of their responses. These users also reported less anxiety about the future after their interactions. In addition, Future You users said the conversation felt sincere and that their values and beliefs seemed consistent in their simulated future identities.

“This work forges a new path by taking a well-established psychological technique to visualize times to come — an avatar of the future self — with cutting edge AI. This is exactly the type of work academics should be focusing on as technology to build virtual self models merges with large language models,” says Jeremy Bailenson, the Thomas More Storke Professor of Communication at Stanford University, who was not involved with this research.

Building off the results of this initial user study, the researchers continue to fine-tune the ways they establish context and prime users so they have conversations that help build a stronger sense of future self-continuity.

“We want to guide the user to talk about certain topics, rather than asking their future selves who the next president will be,” Pataranutaporn says.

They are also adding safeguards to prevent people from misusing the system. For instance, one could imagine a company creating a “future you” of a potential customer who achieves some great outcome in life because they purchased a particular product.

Moving forward, the researchers want to study specific applications of Future You, perhaps by enabling people to explore different careers or visualize how their everyday choices could impact climate change.

They are also gathering data from the Future You pilot to better understand how people use the system.

“We don’t want people to become dependent on this tool. Rather, we hope it is a meaningful experience that helps them see themselves and the world differently, and helps with self-development,” Maes says.

The researchers acknowledge the support of Thanawit Prasongpongchai, a designer at KBTG and visiting scientist at the Media Lab.