3 Questions: Using AI to help Olympic skaters land a quint

MIT Sports Lab researchers are applying AI technologies to help figure skaters improve. They also have thoughts on whether five-rotation jumps are humanly possible.

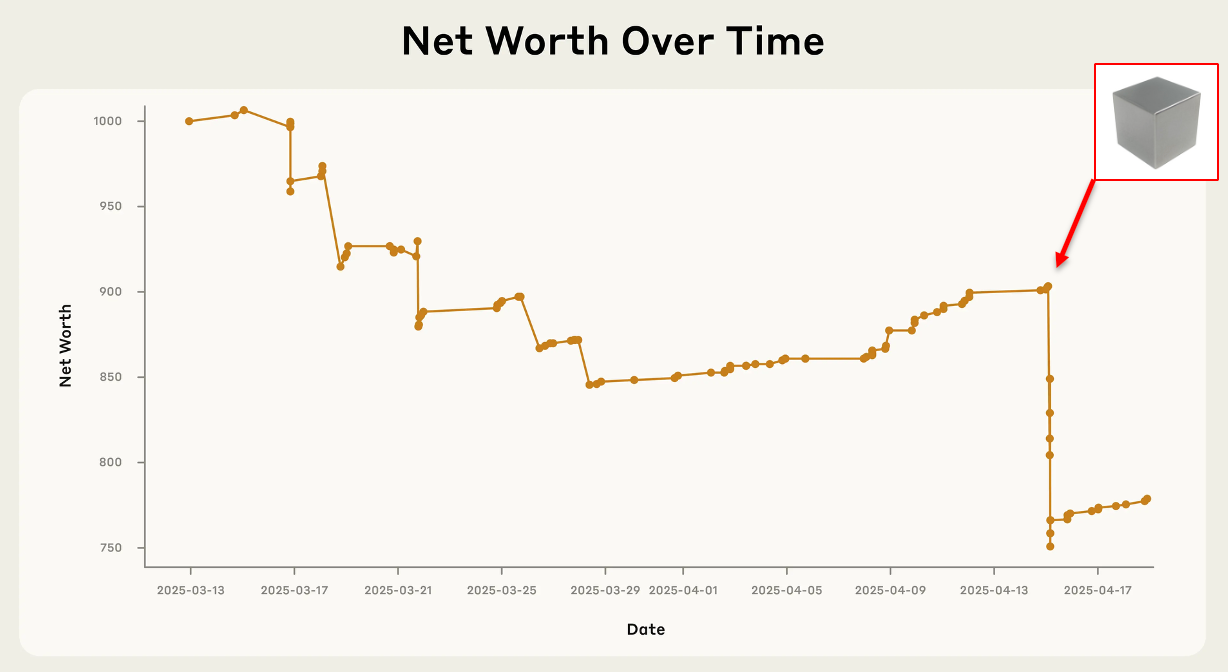

Olympic figure skating looks effortless. Athletes sail across the ice, then soar into the air, spinning like a top, before landing on a single blade just 4-5 millimeters wide. To help figure skaters land quadruple axels, Salchows, Lutzes, and maybe even the elusive quintuple without looking the least bit stressed, Jerry Lu MFin ’24 developed an optical tracking system called OOFSkate that uses artificial intelligence to analyze video of a figure skater’s jump and make recommendations on how to improve. Lu, a former researcher at the MIT Sports Lab, has been aiding elite skaters on Team USA with their technical performance and will be working with NBC Sports during the 2026 Winter Olympics to help commentators and TV viewers make better sense of the complex scoring system in figure skating, snowboarding, and skiing. He’ll be applying AI technologies to explain nuanced judging decisions and demonstrate just how technically challenging these sports can be.

Meanwhile, Professor Anette “Peko” Hosoi, co-founder and faculty director of the MIT Sports Lab, is embarking on new research aimed at understanding how AI systems evaluate aesthetic performance in figure skating. Hosoi and Lu recently chatted with MIT News about applying AI to sports, whether AI systems could ever be used to judge Olympic figure skating, and when we might see a skater land a quint.

Q: Why apply AI to figure skating?

Lu: Skaters can always keep pushing, higher, faster, stronger. OOFSkate is all about helping skaters figure out a way to rotate a little bit faster in their jumps or jump a little bit higher. The system helps skaters catch things that perhaps could pass an eye test, but that might allow them to target some high-value areas of opportunity. The artistic side of skating is much harder to evaluate than the technical elements because it’s subjective.

To use mobile training app, you just need to take a video of an athlete’s jump, and it will spit out the physical metrics that drive how many rotations you can do. It tracks those metrics and builds in all of the other current elite and former elite athletes. You can see your data and then see, “This is how an Olympic champion did this element, perhaps I should try that.” You get the comparison and the automated classifier, which shows you if you did this trick at World Championships and it were judged by an international panel, this is approximately the grade of execution score they would give you.

Hosoi: There are a lot of AI tools that are coming online, especially things like pose estimators, where you can approximate skeletal configurations from video. The challenge with these pose estimators is that if you only have one camera angle, they do very well in the plane of the camera, but they do very poorly with depth. For example, if you’re trying to critique somebody’s form in fencing, and they’re moving toward the camera, you get very bad data. But with figure skating, Jerry has found one of the few areas where depth challenges don’t really matter. In figure skating, you need to understand: How high did this person jump, how many times did they go around, and how well did they land? None of those rely on depth. He’s found an application that pose estimators do really well, and that doesn’t pay a penalty for the things they do badly.

Q: Could you ever see a world in which AI is used to evaluate the artistic side of figure skating?

Hosoi: When it comes to AI and aesthetic evaluation, we have new work underway thanks to a MIT Human Insight Collaborative (MITHIC) grant. This work is in collaboration with Professor Arthur Bahr and IDSS graduate student Eric Liu. When you ask an AI platform for an aesthetic evaluation such as “What do you think of this painting?” it will respond with something that sounds like it came from a human. What we want to understand is, to get to that assessment, are the AIs going through the same sort of reasoning pathways or using the same intuitive concepts that humans go through to arrive at, “I like that painting,” or “I don’t like that painting”? Or are they just parrots? Are they just mimicking what they heard a person say? Or is there some concept map of aesthetic appeal? Figure skating is a perfect place to look for this map because skating is aesthetically judged. And there are numbers. You can’t go around a museum and find scores, “This painting is a 35.” But in skating, you’ve got the data.

That brings up another even more interesting question, which is the difference between novices and experts. It’s known that expert humans and novice humans will react differently to seeing the same thing. Somebody who is an expert judge may have a different opinion of a skating performance than a member of the general population. We’re trying to understand differences between reactions from experts, novices, and AI. Do these reactions have some common ground in where they are coming from, or is the AI coming from a different place than both the expert and the novice?

Lu: Figure skating is interesting because everybody working in the field of AI is trying to figure out AGI or artificial general intelligence and trying to build this extremely sound AI that replicates human beings. Working on applying AI to sports like figure skating helps us understand how humans think and approach judging. This has down-the-line impacts for AI research and companies that are developing AI models. By gaining a deeper understanding of how current state-of-the-art AI models work with these sports, and how you need to do training and fine-tuning of these models to make them work for specific sports, it helps you understand how AI needs to advance.

Q: What will you be watching for in the Milan Cortina Olympics figure skating competitions, now that you’ve been studying and working in this area? Do you think someone will land a quint?

Lu: For the winter games, I am working with NBC for the figure skating, ski, and snowboarding competitions to help them tell a data-driven story for the American people. The goal is to make these sports more relatable. Skating looks slow on television, but it’s not. Everything is supposed to look effortless. If it looks hard, you are probably going to get penalized. Skaters need to learn how to spin very fast, jump extremely high, float in the air, and land beautifully on one foot. The data we are gathering can help showcase how hard skating actually is, even though it is supposed to look easy.

I’m glad we are working in the Olympics sports realm because the world watches once every four years, and it is traditionally coaching-intensive and talent-driven sports, unlike a sport like baseball, where if you don’t have an elite-level optical tracking system you are not maximizing the value that you currently have. I’m glad we get to work with these Olympic sports and athletes and make an impact here.

Hosoi: I have always watched Olympic figure skating competitions, ever since I could turn on the TV. They’re always incredible. One of the things that I’m going to be practicing is identifying the jumps, which is very hard to do if you’re an amateur “judge.”

I have also done some back-of-the-envelope calculations to see if a quint is possible. I am now totally convinced it’s possible. We will see one in our lifetime, if not relatively soon. Not in this Olympics, but soon. When I saw we were so close on the quint, I thought, what about six? Can we do six rotations? Probably not. That’s where we start to come up against the limits of human physical capability. But five, I think, is in reach.